Reviewer Vivien Baumert - FBK-ISIG

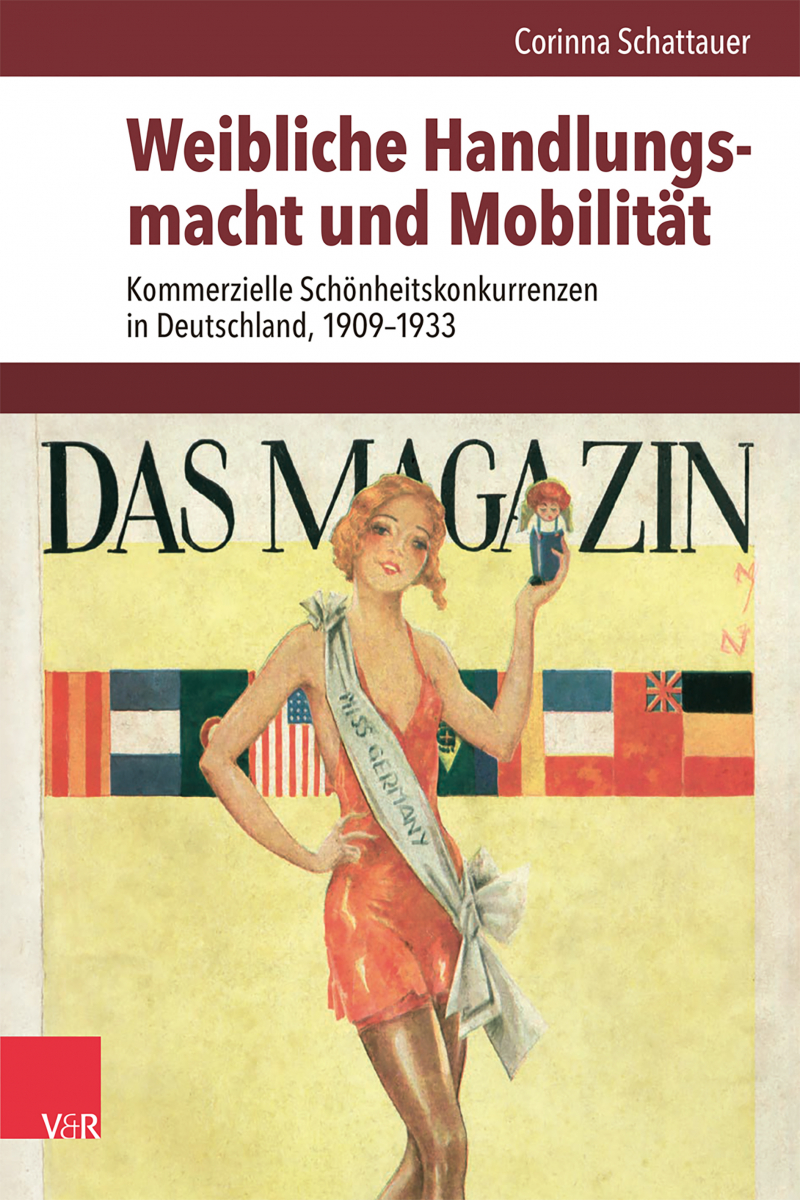

CitationIn her short 2015 discussion of Weimar gender history’s research tendencies, which then began to shift from themes such as «family, sexuality and reproduction» to broader socio-political issues, Marti Lybeck highlighted – though not primarily – the potential of particular topics. Corinna Schattauer’s doctoral dissertation on female agency and mobility in commercial beauty competitions (1909–1933) does not concern itself with Weimar as a state, with its structural and political issues that dominate the correlating historiography. It is particular, however, because it examines the early stages of a specific repeating event in a broader cultural, social, and at times political context, adding to Lybeck’s suggestion «for a new synthesis of Weimar women’s or gender history»[1].

As correctly claimed by the author, the book is the very first systematic historical study of German beauty contests and their transference into the everyday lives of contemporary German citizens (p. 20). Schattauer, who has a professional background in film-making, museum work and corporate history, aims to analyze the possibilities and limits of female agency in commercial beauty contests as well as women’s methods of acquiring spatial and social mobility from a local, national and transnational perspective (p. 24). The chosen time frame of 1909 to 1933 marks the period from the first beauty contest in the German Kaiserreich until their restriction and prohibition by the NS regime. Schattauer explicitly states the intention to avoid a «teleological Narration» leading up to National Socialism (p. 18), which, unexpectedly, she manages quite well by circumventing the strictly chronological approach and instead structuring the analysis in spatial and social categories, thereby focusing on the relevant historical actors.

Schattauer divides her study into three parts: «Handlungsräume» (Spaces of Action), «Handlungspielräume» (Scopes of Action) and «Raumwechsel» (Change of Space). While in English we are tempted to summarize space and scope of action within the concept of agency, in German historiography linguistically and analytically differentiating between the two is a common method for exploring the real working grounds of historical (gendered) actors. In «Handlungsräume» (pp. 41-112) Schattauer lays the critical groundwork for her in-depth analysis, outlining beauty contests as a practical space within which women could act. This includes localizing forms and mouthpieces of female beauty comparisons and competitions in daily life, surveying their quasi-institutional development beginning in 1909, and briefly considering other related beauty practices, such as male muscle contests (p. 15).

Having contextualized the space and practical value beauty contests potentially represented, Schattauer then moves on to the core analysis and the question of how and to what extent women, that is beauty queens and their fellow participants, could utilize and regulate the beauty contest complex to their own advantage (pp. 113-230). The analytical pattern Schattauer engages in this and the following chapter aims to first depict societal expectations and narratives before comparing them with real stories and lining them with extensive source material. Against this backdrop, she identifies a powerful field of tension women had to navigate, combining autonomy and heteronomy, consuming and allowing to be consumed (p. 181). Schattauer pays special attention to the relation of individual goals and representative roles former contest participants and beauty queens actively and passively pursued and embodied, national ascriptions being the most prominent (pp. 203-230). At this point, the text lacks a brief summary of the identified Handlungsspielräume to enable the reader to connect scopes of action and questions of mobility, the latter following in the final chapter. «Raumwechsel» closely examines how women used the beauty queen career path to generate «Mobilitätskapital» (Mobility Capital) (p. 229), again inspecting societal – mainly literary – expectations as well as real careers.

Schattauer perceives and plausibly explains gender in this instance as a performative act, a resource especially lower-class women could actively explore to become mobile and increase their economic, social, and symbolic capital (p. 286). She tries to convey a myriad of topic-related aspects, proving her knowledge of the complexity gender history represents. From the reader’s perspective, however, every little excursion into big questions, such as intersectionality, men’s studies or colonialism, somewhat distracts from the original argument. This becomes clear when in most subchapters’ interpretation of the prior argument women actors appear as more of an afterthought.

Nonetheless, by dipping into different but related topics and aspects, Schattauer manages to keep things interesting and diverse: What role did the beauty queen’s mothers play in promoting their daughter’s career and to what end (p. 194)? Looking at other European competitions and global contexts, can we identify something of a European spirit (e. g. p. 92)? Considering the polemics around the objectification and sexualization of female bodies, processing a topic such as this in a linguistically and methodically critical but appropriate, or rather reflective manner is no easy task. The key, as Schattauer and many before her successfully proved, is to view women as actors, not as objects.

[1] M. Lybeck, The Return of the New Woman and Other Subjects of Weimar Gender History, in «Contemporary European History», 24, 2015, 1, pp. 127-137.